Triumph on the Wall

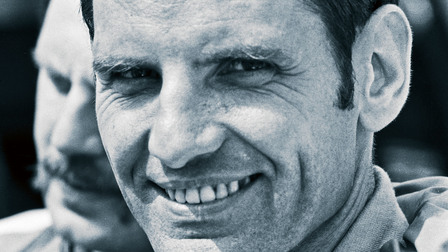

Man in the background: Peter Falk,

Fifty years ago a

It all began over a glass of beer on a summer evening. And any story that begins like that has to be legendary.” That’s precisely what went down in Christophorus number 90 of January 1968. Thus began the article by Swiss race-car driver Rico Steinemann, in which he reported on a dramatic endurance-record drive in Monza. The fiftieth anniversary of the triumph on the banked corners of the Autodromo Nazionale di Monza is now in full swing.

Around the table were Rico Steinemann and his racing colleague Dieter Spoerry. Still in the midst of the 1967 racing season with their

![[+]](https://files.porsche.com/filestore/image/multimedia/none/christophorus-issue383-article13-content-01/normal/40632a39-9486-11e7-b591-0019999cd470/porsche-normal.jpg)

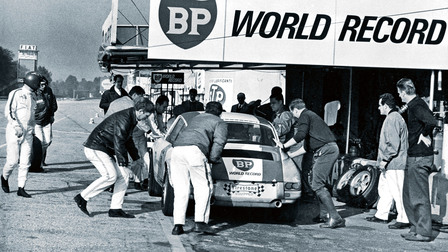

Keeping time: The race officials’ stopwatches continued to run during pit stops.

Exactly sixteen hours is how long the drive from Zuffenhausen to Monza took in the 911 R.

“All races, but especially endurance races, were extremely important to us in order to gain new technical insights,” says Peter Falk, eighty-four, who headed up pre-series and racing development for

Too many bumps

The record chase began on October 29 at the stroke of noon. Jo Siffert was first up. A stint at the wheel lasted one and a half hours, followed by four and a half hours of rest. For the mechanics in the box, the Scout motto “Be prepared!” was the perpetual order of the day. Günter Steckkönig, suspension expert for

![[+]](https://files.porsche.com/filestore/image/multimedia/none/christophorus-issue383-article13-content-02/normal/bbb606d9-9486-11e7-b591-0019999cd470/porsche-normal.jpg)

Approach: The conditions are milder than back then: the detour is gladly taken.

Expertise in the pit: Suspension expert Günter Steckkönig was part of the

That meant the end of the show after just about twenty hours. The rules of the international motorsports federation FIA stipulated that all spare parts in an endurance record attempt had to be carried in the car. All that was allowed in the pit were spare wheels, jacks, spark plugs, gasoline, and oil. The team had been ready for everything, except for the astonishingly poor condition of the two banked curves in Monza: the concrete walls built in 1954 with inclines of up to 45 degrees had potholes the size of soccer balls. “It was like a washboard,” says Steckkönig. It was, in any event, too violently bumpy for a lightweight race car like the

A few hours later Bäuerle called in from the Swiss border: the Swiss police wouldn’t allow the car into the country, deeming it too loud. There was only one thing Bäuerle could do: make a furious, all-night detour around Switzerland via Lyon, Grenoble, and Turin on the way down to Monza. Peter Falk and engine expert Paul Hensler, who had both embarked in the other 911 R after Bäuerle’s call, naturally opted for the more direct route through Austria and over the Brenner Pass. They arrived on Tuesday morning; by then the other 911 R had already been dismantled. The spare parts were ready for action.

Half a century later, the drive is considerably easier. Johan-Frank Dirickx and Bart Lenaerts don’t have to race against the clock; on the contrary, the two can relax and enjoy the pass roads. They pass Lyon and Grenoble in their identical remake, stop a number of times, take a few pictures, and revel in the road trip.

![[+]](https://files.porsche.com/filestore/image/multimedia/none/christophorus-issue383-article13-content-03/normal/27b86ad9-9487-11e7-b591-0019999cd470/porsche-normal.jpg)

96 hours: Fifty years ago, over four days on the high-speed oval in Monza, the

Trying conditions: Fog, cold, and heavy rains made the record drive in Monza a grueling test of nerves.

Fifty years ago the situation was much different: it was dark and raining cats and dogs when the record attempt was restarted at 8:00 p.m. on Tuesday evening. Right away, in the first few hours, there were difficulties with iced-up carburetors, but the BP colleagues resolved that with an injection additive. To help protect the suspension, Peter Falk spent the afternoon marking the biggest potholes on the banked walls with long white arrows on the track. This enabled the drivers to take the potholes between the wheels and thus avoid the most bone-jarring bumps. It worked. The 911 R went about its business with its familiar roar, the rain stopped, and Wednesday and the second night passed without incident. The pit stops took little more than a minute. Ninety liters of gasoline, top off the oil, clean the windshield, check the suspension—it was literally a well-oiled machine in action. Not that the 911 R emerged entirely unscathed from its ordeal: damage to the front damper struts on both sides necessitated a pit stop, where once again Steckkönig and the mechanics repaired the sports car in a flash. In accordance with regulations, the 911 R had the spare damper struts on hand.

It was wet again on Thursday evening. The problem this time was that there were no more rain tires. So the Firestone experts cut rain grooves into the dry tires by hand. The drive continued through the night and the rain, guided by battery-powered lamps on the banked curves’ lower boundaries that gave the drivers at least some range of vision at over 200 kmh. “I still remember how driver Charles Vögele sat there in the pit after his stint, absolutely exhausted, recounting how he had been driving into the banked corners almost completely blind,” recalls Steckkönig. “Those were some tough guys.” The ristorante at the Autodromo was open around the clock during the record attempt. “One time I ordered breakfast at eight in the evening,” recalls Rico Steinemann.

On Friday evening, the tension reached a fever pitch. Had the grueling ordeal paid off? At around 7:00 p.m. it was confirmed: they’d driven 15,000 kilometers at a new record average speed of 210.22 kmh. Not long after that,

Today the 911 R still feels great on the venerable old track: Dirickx and Lenaerts do their laps with the classic 911. Without rain tires, but with a bit of fall foliage whipping up around the purist sports car. The

By Sven Freese

Photos by Lies De Mol

BP world record drive in 1967

Place: Autodromo Nazionale di Monza

Record attempt start time: October 31, 8:00 p.m.

End of record attempt: November 4, 8:00 p.m.

Vehicle:

![[+]](https://files.porsche.com/filestore/image/multimedia/none/christophorus-issue383-article13-margin-01/normal/178c9339-9486-11e7-b591-0019999cd470/porsche-normal.jpg)

![[+]](https://files.porsche.com/filestore/image/multimedia/none/christophorus-issue383-article13-margin-02/normal/6192b599-9486-11e7-b591-0019999cd470/porsche-normal.jpg)

![[+]](https://files.porsche.com/filestore/image/multimedia/none/christophorus-issue383-article13-margin-03/normal/f733a419-9486-11e7-b591-0019999cd470/porsche-normal.jpg)

![[+]](https://files.porsche.com/filestore/image/multimedia/none/christophorus-issue383-article13-margin-04/normal/7041b139-9487-11e7-b591-0019999cd470/porsche-normal.jpg)

![[+]](https://files.porsche.com/filestore/image/multimedia/none/christophorus-issue383-article13-margin-05/normal/9cb8a079-9487-11e7-b591-0019999cd470/porsche-normal.jpg)