Shift down a gear. Browse and enjoy.

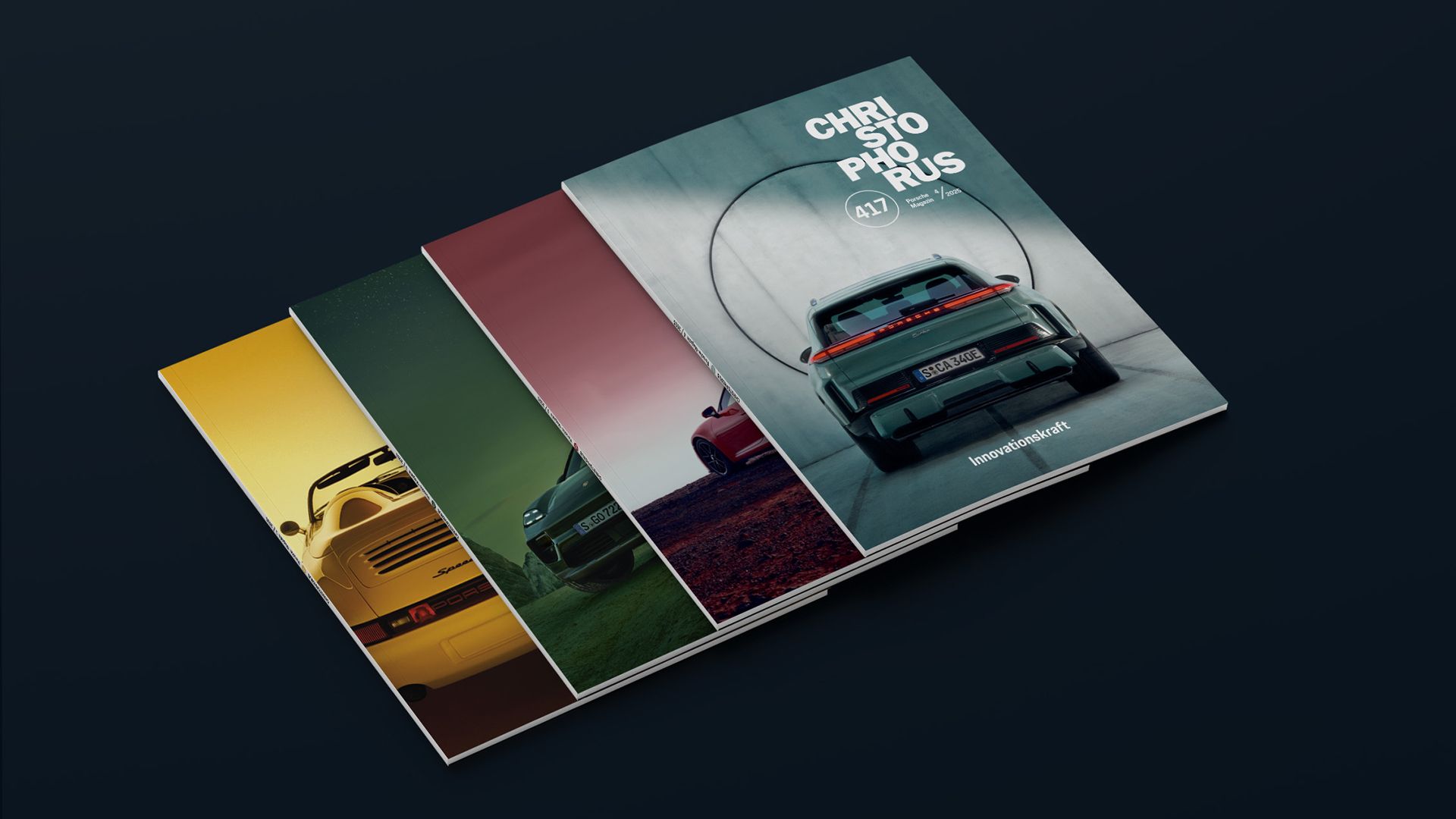

Exclusive, unique, inspiring: Christophorus is the magazine for Porsche enthusiasts. And almost as old as the sports car brand itself. Ever since the first issue in 1952, the publication has been inspiring its readers with stories about the Porsche company – with personalities, products, history, and motorsport.

The print edition of the Porsche magazine is published four times a year in 10 languages worldwide, with a print run of around 600,000 copies per issue. Christophorus is considered one of the most prestigious corporate magazines worldwide. Historical copies are highly collectible.

Issue #417

The Energy of Community

Registro Italiano E-motion is the world’s first Porsche club for purely electric sports cars. The first joint outing took place in September, with 73 electric vehicles taking part. The dawn of a new era for the Porsche community.

Subscribe

Four issues of Christophorus are published each year; available by subscription for 24 euros.

)