The sea is wild, the sky is gray, and the temperature is 25 degrees Celsius. But it’s only six in the morning. In half an hour the sun will rise for the race to its zenith, burning with the strongest UV radiation on earth, before descending again precisely twelve hours later.

![[+]](https://files.porsche.com/filestore/image/multimedia/none/christophorus-issue387-article04-content-01/normal/efbe725f-6f24-11e8-bbc5-0019999cd470/porsche-normal.jpg)

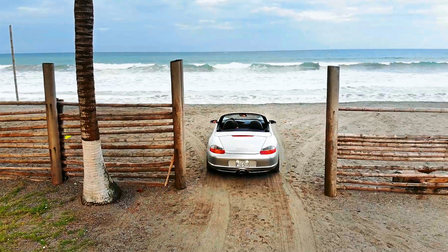

Starting point: The Pacific coast near Pedernales.

This is where the equator meets Ecuador. One hundred kilometers later, the road passes through the woods as it ascends into the Andes.

0 feet above sea level, 0 degrees latitude, 0 miles/distance

The silver-gray

Quito, the capital, is around three hundred kilometers and 2,850 meters of elevation away. Galardo came down from there the evening before. It was already dark when he arrived, with hungry mosquitoes buzzing around the pool. The hotel proprietor warned against parking under the palms: beware of coconuts. Now the

![[+]](https://files.porsche.com/filestore/image/multimedia/none/christophorus-issue387-article04-content-03/normal/2999cf7e-731a-11e8-bbc5-0019999cd470/porsche-normal.jpg)

Pit stop:

Six dollars buys a full menu—and a view of the mountain stream is included free of charge.

He accelerates. Alas, on the road to Pedernales, a small city just a few kilometers north of the equator, the speed limit is an unsatisfying 100 kmh. Indeed, it’s not permitted to drive faster anywhere in Ecuador—not even on the many new eight-lane highways. If the offerings of the road system in Ecuador are generous, its official speed-minders are anything but: zero tolerance is the policy here. Even speeds barely above the 100 kmh limit can result in sizable fines. So Galardo applies the brakes almost as soon as he starts speeding up. He’s still in the Costa, the fertile lowlands along the coast and the country’s fourth geographic region, alongside the Andean Highlands, the Amazon basin, and the Galápagos Islands.

The road rises gently as it wends its way through plantations and bamboo forests. Here and there, mechanical diggers burrow their way deep into the ground: El Dorado beckons. Gold diggers are in search of what they hope will make them rich and powerful. At the moment they’re still working for the standard minimum wage of US$ 386 a month. In 2000 Ecuador abandoned its national currency, the sucre, and replaced it with the U.S. dollar. The move has made it easier to export oil, bananas, and cut flowers—not to mention the country’s biodiversity, which could prove a winning business model. Ecuador, after all, boasts the highest biodiversity in the world relative to its size. On the Galápagos Islands: giant tortoises, lizards, sea lions. Off the mainland coast from June through September: thousands of mating humpback whales. Along the coast: iguanas, parrots, and monkeys. In the highlands: condors and vicuñas, the largest birds of prey and smallest camels in the world, respectively. And in the Amazon basin on the other side of the mountains: tapirs, jaguars, parrots, piranhas, and more insect species than in all of Europe.

4,921 feet above sea level, 0 degrees latitude, 124 miles/distance

The provincial town of Mindo lies below. Ahead of the

Nice and cool:

At 2,850 meters above sea level, Quito is nearly on the equator. In other words, expect shortness of breath—and you might want to check the oil level again.

9,350 feet above sea level, 0 degrees latitude, 178 miles/distance

The highest capital in the world has 1.5 million inhabitants and thin air—which means heavy breathing for lowlanders—and is Ecuador’s most beautiful city. Cool summer air, steep cobblestone roads, colonial architecture, luxury hotels, coffee shops, ice cream vendors. Galardo has made a beeline to a gas station in the suburb of Cumbayá, where

![[+]](https://files.porsche.com/filestore/image/multimedia/none/christophorus-issue387-article04-content-02/normal/f2367869-6f25-11e8-bbc5-0019999cd470/porsche-normal.jpg)

15,282 feet above sea level, 0°41´3˝ S latitude, 230 miles/distance

The

![[+]](https://files.porsche.com/filestore/image/multimedia/none/christophorus-issue387-article04-margin-04/normal/1f379d39-6f26-11e8-bbc5-0019999cd470/porsche-normal.jpg)

Highlight:

The active volcano Cotopaxi is just sixty kilometers from Quito. Whenever it erupts, it rains ash over the capital.

6,234 feet above sea level, 0°44´9˝ S latitude, 342 miles/distance

Back down again. The Amazon basin. The primeval forest. The Río Victoria cuts deep into the bedrock. Waterfalls plunge into the depths from the opposing cliff. Fog rises from the peaks. The Andes have been crossed. Now the sports-car convoy is in the country’s wild east, driving down to the roadblock in Baeza. Special police units have set up a checkpoint. A traffic jam forms. The

End of the excursion: Diego Guayasamin (right) designed the UNASUR building. The

9,350 feet above sea level, 0 degrees latitude, 404 miles/distance

Back in Quito, the parade of

By Michael Kneissler

Photos Luca Zanetti, Dani Tapia (drone)

![[+]](https://files.porsche.com/filestore/image/multimedia/none/christophorus-issue387-article04-margin-02/normal/50078165-6f25-11e8-bbc5-0019999cd470/porsche-normal.jpg)

![[+]](https://files.porsche.com/filestore/image/multimedia/none/christophorus-issue387-article04-margin-03/normal/a71bf76f-6f25-11e8-bbc5-0019999cd470/porsche-normal.jpg)

![[+]](https://files.porsche.com/filestore/image/multimedia/none/christophorus-issue387-article04-margin-01/normal/879eb5a3-6f24-11e8-bbc5-0019999cd470/porsche-normal.jpg)